Pa Ranjith’s latest boxing drama ‘Sarpatta Parambarai,’ which released on Amazon Prime Video on July 22, has received massive attention from the audience and is being touted as one of the most successful boxing films out of India.

While the period film set in the 1970s mainly focuses on the clash between two rival boxing clans, the life of Kablian (played by actor Arya) as a boxer, and touches upon the caste issues and politics during the Emergency, it ends up doing much more than that. Sarpatta Parambarai brings into attention one of the lesser-known traditions of North Madras: professional boxing.

Once part of a thriving culture, professional fighting in North Chennai flourished amongst the working-class sections of what was then North Madras. Up until the 70s and 80s, it was part of everyone’s life, with the sport drawing huge numbers of crowds, and trained boxers from the area fighting to win large sums of prize money.

History of boxing in North Madras

It was during the British era that modern boxing, also called ‘Kuthu Sandai’, was introduced to Madras. Until then, Tamil Nadu was known for martial art forms such as Silambam (stick fighting).

In the areas of Royapuram, Washermenpet, Pulianthope and Harbour lived working-class manual labourers, and members of the fishermen community. The area was also home to the British and Anglo-Indians and was often described as “mini London”.

The British and Anglo-Indians in Madras popularised boxing solely for their entertainment purposes. Soon, the locals began developing an interest in boxing and nursed a desire to beat the British in their own game.

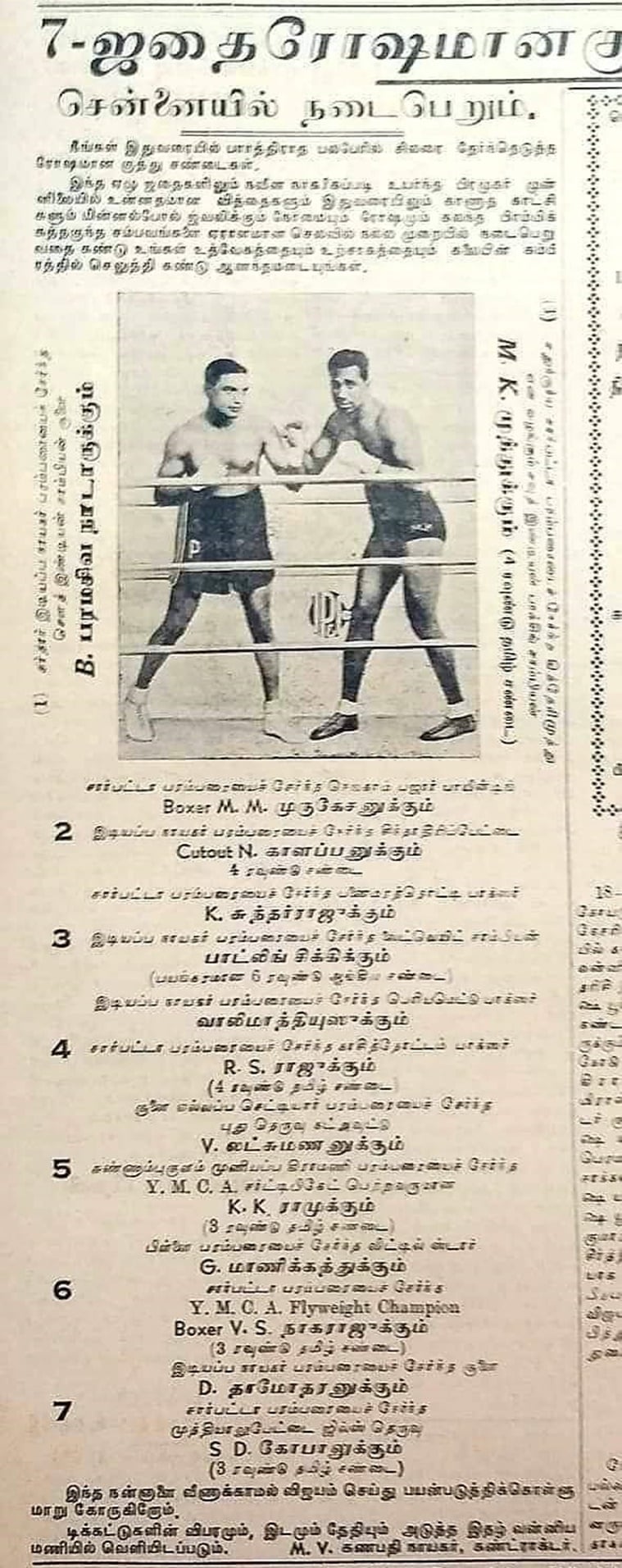

Nat Teri, a Black British, was one of the most undefeated boxers in south India. In 1942, Teri defeated Arunchalam, one of the first local boxers, who died during the fight. Post this, another match was set up where M Kitheri Muthu, one of the earliest boxers of the Sarpatta Parambarai, was chosen to fight Teri. For the match against Teri, Muthu was given intense training after which he beat Teri.

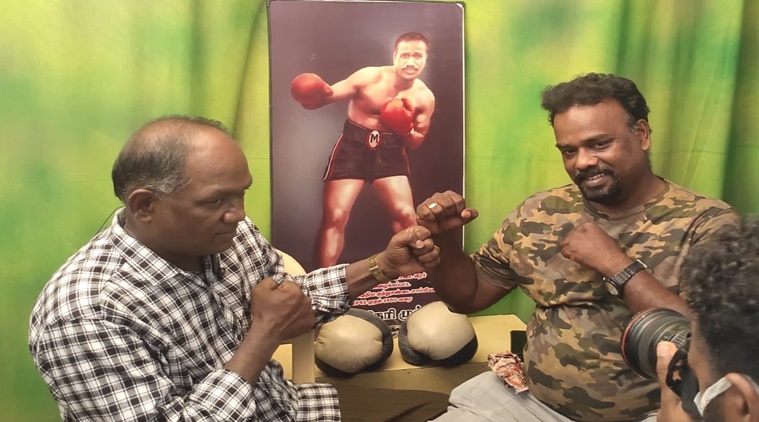

Kitheri Muthu and his brother Chinna Muthu

“The victory of my grandfather was widely celebrated in all areas and that is when people began to take boxing seriously. The fact that a local beat the British in boxing was a matter of pride for all the people,” said Kitheri Muthu’s grandson Anand, a former boxer himself. The keenness to beat the British in boxing was what made many take greater interest in the game, he added.

By now, professional boxing had become a serious affair and public matches were organised on a regular basis, with tickets costing in the range of Rs 5- Rs 15.

Anand believed that boxing came naturally to the people of North Madras since most of them had well-built physiques, as they were manual labourers and fishermen. “Their muscles were already well developed.”

The big Parambarais of boxing

The word ‘Parambarai’ (lineage/clan in English) was a word often associated to signify the different clans in boxing in North Madras. While the exact year and origin of when the Parambarai culture in boxing began is unclear, it is said that the Sarpatta Parambarai was one of the first clans of boxing that was formed.

Post 1940s, several boxing clubs started across different areas. Panaimara Thotti in Royapuram became the epicentre of boxing.

The main ‘Parambarais’ in boxing are the Sarpatta Parambarai, Idiyappa Naicker Parambarai and the Ellappa Chettiyar Parambarai. These clans were mostly based in the area that one lived in. Most of North Chennai including areas such as Royapuram, Washermenpet, Pulainthope, Harbour belonged to the Sarpatta Parambarai, said the locals of the area.

Stephen, another grandson of Kitheri Muthu, who runs the M Kitheri Muthu boxing club in North Chennai, said, “Parambarais are the same as boxing clubs. Sarpatta Parambarai was the largest of all and disintegrated to several other clubs.”

Stephen, grandson of Kitheri Muthu

Stephen, grandson of Kitheri Muthu

While every sport is competitive in its own ways, the rivalry amongst different clans was talked about much. The biggest rivalry was between the Sarpatta Parambarai and the Idiyappa Naicker Parambarai. Boxers from the Idiyappa Naicker and Ellapa Chettiyar Parambarai did not fight against each other because they stayed in the same region and trained together.

“They are like brothers. Their main aim was to defeat boxers from the Sarpatta Parambarai,” Anand said. Every boxer owes allegiance to the Parambarai that he belongs to, he said. When asked whether caste plays an important role in a boxer joining a particular clan, Anand said it did not. “In the Sarpatta Paramabarai, we had people from across different communities. We had fishermen, Dalits, Muslim, Christians, Hindus. There was really no caste discrimination,” he said.

While some believe that the Idiyappa Naicker Parambarai and the Ellappa Chettiyar Parambarai selected boxers based on the caste, since ‘Naicker’ and ‘Chettiyar’ are caste names, many like 70-year-old Baktavachalam strongly disagree. Baktavachalam was a famous boxer whose career spanned a two-decade period starting 1969. In 1960, when he got interested in boxing and asked his workplace if he could get trained, the first response he got from his boss was “you people are not fit for boxing.” Offended, Baktavachalam relentlessly pursued his boss and asked him for one chance. Despite no training, he knocked out his opponent in the ring in the first round. Shocked by his match, a boxing teacher agreed to coach him.

Baktavachalam said, “At the end of the day, more than caste, religion and community, it is your talent, eagerness to learn and ability to perform in the ring that matters”.

The 1970s-80s boxing craze and its subsequent ban

There are two types of boxing — amateur and professional. Amateur boxing meant fighting for medals, awards, and certificates in the state and national level. But, the craze in North Madras was professional boxing.

“Professional boxing is a business, involves a lot of money,” said Arjuna awardee, Olympian and international amateur boxing champion Venkatasa Devarajan.

Venkatasa Devarajan

Venkatasa Devarajan

Professional boxing, especially since the late 60s, became a big business. Prize fighting bouts attracted more than 15,000 people and matches took place in big venues like Nehru Stadium and Scouts Ground. The bigger the crowd, the more tense the fights became, reminisced Baktavachalam.

The matches used to take place on a contract basis and the main organisers of the event were the contractors. “Every boxer signs a contract for, say 2-3 matches. Anytime the contractor asks them to fight, they must be ready to,” Devarajan said. He said the more the boxer wins, the higher his pay would be. Contractors were also involved in scheduling the date, venue of the matches and would ask the police and government for a permit licence.

Through the 1970s, professional boxing also became a pop culture in Madras. Top stars and politicians including the then chief minister MG Ramachandran and actor-politician MR Radha were also influenced by these boxers. The then governments, too, encouraged boxing matches and started to give permission for them.

“Normally you would think it is the common people who are influenced by movie stars. But, it was actually the stars who got inspired by boxers. They would come regularly to meet with the boxers and learn from them. MGR even took inspiration from Kitheri Muthu for a fight sequence in one of his films,” Anand said.

Newspaper article on Kitheri Muthu

Newspaper article on Kitheri Muthu

Boxing ultimately became a part of the culture and tradition of North Madras. The frequency of matches began to increase and so did the crowd. However, the more boxing and the boxers became popular, the more controversy it began to create.

“Since there was a lot at stake for the boxers and the Parambarai’s, people did not want to accept defeat and so they began fixing the match in advance,” Stephen said.

The rivalry between different Parambarais became more evident post the Emergency period in 1975. The biggest issue the community faced was the fights between supporters belonging to different clans. This became more frequent during and post the Emergency in 1975. “The public started to see the boxers as real-life heroes. It became tough for them to accept their hero’s defeat. If their boxer loses the match, the entire atmosphere would become tense, fights would break out and there would be a lot of ruckus in the arena. They would throw chairs at one another and damage property,” Stephen said.

“The rivalry between boxers was not as much as people claim it to be. It was there in the ring for sure. We were all friends outside the ring,” said Baktavachalam. He also narrated an incident that took place during one of his matches, when he was fighting against another famous boxer Sundarrajan. After he beat Sundarrajan, who was much senior to him, he bowed down and touched his feet as a mark of respect.

A former boxer, who fought during the 1970s and who did not want to be named, said, “many boxers were lured in by politicians with gifts of money. It was a lot easier for boxers to get permission for matches if they were associated with a party. They would get it at cheaper rates.” Many also believed that a lot of boxers took the wrong path of entering rowdyism and began to act like henchmen for politicians and misused their physical power as boxers.

Not everyone agrees. Stephen said there was a wrong perception that all boxers were henchmen. “Just because one or two of them got into the wrong hands, does not mean everyone was like that. Boxers are extremely disciplined people,” he said. One of the first rules in boxing, Stephen said, was that boxing should be done only inside the ring. “Anyone who got involved in other activities would immediately be sent out,” he said.

Baktavachalam and Devarajan echoed this, and added that most boxers were extremely soft and disciplined people. “While boxers look and act very tough, they are actually very disciplined. Discipline was very important for the profession,” Devarajan said.

A shift from professional boxing

Due to law and order issues, there was an unofficial ban on professional boxing in the state, post which many left the profession. There was also a huge shift from professional boxing to amateur boxing.

After their peak fighting days got over, many boxers started taking up government jobs in railways and other private places. “Many boxers at a young age would play for five years and settle in their lives after getting government jobs,” Anand said.

Devarajan, who trained under one of the Sarpatta clubs, also began his career in boxing as an amateur. He went on to win the bronze medal in the 1994 World Boxing Championship, and is today a boxing coach.

As soon as the ‘Parambarai’ concept began vanishing, former boxers became coaches and started their own boxing schools. Anand and Stephen started a boxing school in the name of their grandfather and till today provide free boxing coaching for students in the north Chennai area.

Speaking about how boxing is still part of their culture in North Chennai, Devarajan said, “You will see that all boxers have a connection with the field. They would have trained their sons and daughters in it too. Everyone is very attached to boxing and we are using coaching centers to continue doing what we are passionate about.”

Anand and Stephen believed that even today boxing remains a very important sport that needs to be taught to people. They said that it was the need of the hour and must be treated as any other sports profession. Even now, the area of north Chennai witnesses boxing fights amongst clubs. This is more at the amateur level.

“We train the students so that they can represent the district of the state,” Anand said.

Baktavachalam also trains 3-4 boys in his locality and said, “I am a sportsperson, and this is my passion. My only goal is to continue to share my knowledge and expertise with others, as long as I am alive, because boxing will always be a part of me.”

Stephen added that the golden days of professional boxing will always be etched in their memories as stories. He is not sure if professional boxing will return to Chennai, but he wished that instead of placing a blanket ban on professional boxing, the government must streamline and regulate boxing.

“Only when the ban is lifted and there is better regulation, boxing will rise again in the state,” he said.

Source: https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/chennai/sarpatta-parambarai-bring-north-madras-boxing-memories-back-in-the-ring-7441714/